LIFE AS MYTH

![]()

JOURNAL

![]()

JOURNAL 2015

1001 stories

The gift of self

![]()

SUMMER 2015

Navigating dark waters

![]()

LIFEWORKS

![]()

ATLAS

![]()

SUMMER 2015

NAVIGATING DARK WATERS

Orpheus. Odilon Redon. 1905. The Munch Museum. Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco.

First, a story.

Orpheus (meaning the darkness of night) was a poet whose music was so enchanting that he could charm all creation when he sang and played his lyre. Eurydice (meaning wide justice) was an oak nymph and the daughter of the sun-god Apollo.

Eurydice and Orpheus fell deeply in love. On their wedding day, Eurydice danced across a meadow while Orpheus played on his lyre. During the dance, a viper bit her heel and she died. The loss of his bride was so profound that Orpheus descended into the underworld to beg the gods to release her, petitioning Hades and Persephone through song. His music was extremely sorrowful, the story says, bringing tears to the eyes of the gods.

Hades agreed to return Eurydice to Orpheus on one condition: she must walk behind her husband for the entire journey out of the underworld and Orpheus must not look on her face until they had both exited. Despite the warning, just as they neared the surface, Orpheus turned around to make sure that Eurydice was still following him. When he turned, she vanished and Orpheus returned to the land of the living alone.

Why? That's the philosophical question. Why did he turn? Didn't he know what would happen? The most common explanation was that he loved her so completely that he could not risk returning to the world without her. He had to know she was still there, that she was following him. In other words, his heart overruled his reason and he turned to check even though, in doing so, he lost her forever.

That explanation aligns with a traditional narrative structure, one that is deeply embedded in our world. Classical storytelling focuses on male individuation and conquest, and identifies women as trophies, the ultimate reward of the hero. However, I think there could be something far more interesting going on in this particular myth, if we bring a little Zen to it. And a little bit of Rilke.

That was the deep uncanny mine of souls, writes Rainer Maria Rilke as he opens "Orpheus, Eurydice and Hermes," a poem based on this myth. With Rilke and through his poem, we descend into the land of the dead, arriving at the intersection he creates between the death of an old myth and the birth of a new one. That intersection is the point where Eurydice and Orpheus see each other. It is not just that Rilke reimagines the myth of Eurydice and Orpheus, he also radically reimagines the meaning of their parting.

At her death, Eurydice, no longer the bride of Orpheus, becomes instead his muse. Consider. After her death she inspires music of such exquisite beauty that all creation stills to listen and the gods weep. In other words, her absence provides access to greater creative depths than Orpheus had heretofore achieved on his own.

Eurydice, as Rilke describes her, has gone through an irreversible transformation, one that was taking her to an existence far richer than the one she ever knew with Orpheus. The poet writes,

She was no longer that woman with blue eyes

who once had echoed through the poet’s songs,

no longer the wide couch’s scent and island,

and that man’s property no longer.

She was already loosened like long hair,

poured out like fallen rain,

shared like a limitless supply.

She was already root.Eurydice had reached the source. She was no longer able to follow behind and in her husband's footsteps. She was whole; she was subject.

Why? We return to the philosophical question. Why did Orpheus turn? Didn't he know what would happen? I believe that Rilke answers yes -- on some level, Orpheus knew the result of violating the prohibition against looking and that is what he chose. He wanted to lose her. The only way that could happen was to break the one condition that Hades made. I believe that Hades gave Orpheus a choice, already understanding the transformation in Eurydice and knowing in advance how Orpheus would choose.

Eurydice was now subject and Orpheus, as artist, needed her to remain object, muse, forever a reflection of his desire, never subject, never root.

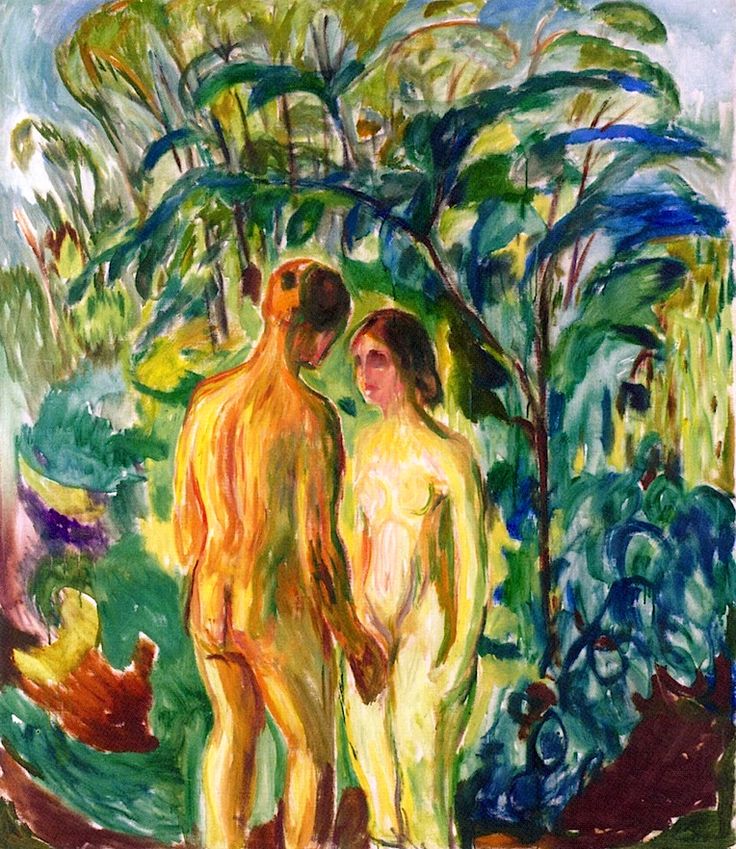

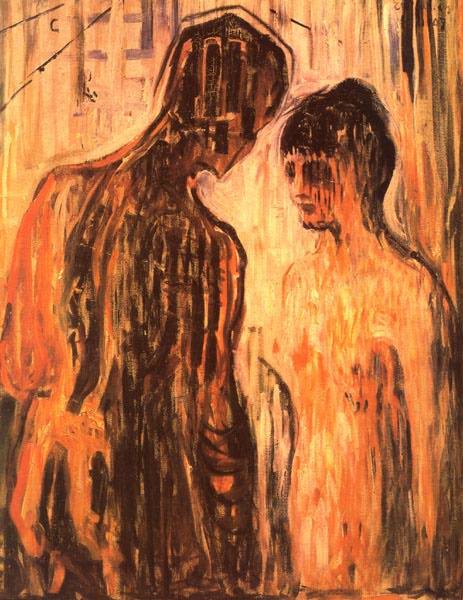

(clockwise) The artist and his model.Edvard Munch. 1921. Naked man and woman in the woods. Munch. 1919-25. Psyche and Cupid. Munch. 1907. The Munch Museum. Oslo, Norway.

Edvard Munch was the second child born to Christian and Laura Cathrine Munch. Munch's mother died of tuberculosis in 1868 and his favorite sister, Johanne Sophie, also died from the disease in 1877. After his mother's death, Christian raised the children in an atmosphere of religious fear, frequently instructing them that if they sinned in any way, they would go to hell without hope of pardon. Munch's younger sister was diagnosed with mental illness at a very young age. Munch himself was also often quite ill. The only one of the five siblings to marry, his brother Andreas, died a few months after the wedding. His father died at an early age as well (1889).

Throughout his life, Munch used his art to come to terms with the death and illness which filled his childhood. The Scream (1893), his best known painting, is characteristic of his early work.

In 1908, suffering from acute anxiety, he received psychiatric treatment and electroshock therapy at the clinic of Dr. Daniel Jacobson. The psychiatric treatment dramatically altered Munch and his work. Around 1909, the artist began to give voice to this change, depicting the healthcare staff and environment along with a new perception of self through vibrant colors and harmonious forms. Returning to Norway after treatment, he revisited old themes of death and loss in his work but Munch's recapitulation also incorporated the changed approach to art, the canvases of the artist now reflecting a transformed interior state. This tension between new approaches and old losses never resolved fully, continuing to emerge in his painting and self-portraiture until the end of his life.

The separation. Edvard Munch. 1896. The Munch Museum. Oslo, Norway. This is one in a series of paintings that expressed the artist's on-going struggle to reconcile the loss of a woman he loved.

SUMMER 2015

THE DARK SIDE OF THE SUN

Lunar eclipse. NASA.

The lunar eclipse occurs when the earth aligns exactly, or almost exactly, between the moon and the sun, causing the earth's shadow to fall across the surface of the moon. In the peak viewing areas this year, the eclipse rendered the moon blood red. This extraordinary and natural spectacle has inspired multiple mythological explanations. It is even one of the visionary omens in the prophetic texts of Revelation: And I behold when he had opened the sixth seal, and lo, there was a great earthquake; and the Sun became black as sackcloth of hair, and the Moon became as blood. Revelation 6:12 KJV

Various traditions credit lunar and solar eclipses with affecting human and natural events. Tibetan Buddhists say that during a lunar eclipse, our actions, whether good or bad, are multiplied one thousand fold. Astrologers say the occurrence of an eclipse can trigger wars, political events and natural phenomenon (e.g., earthquakes).

In 1503 Columbus' ships ran aground in Jamaica. During the year that Columbus and his crew waited for rescue, the natives took care of them. Eventually, however, the islanders tired of feeding them. Columbus had an almanac and knew of an upcoming lunar eclipse. Just before the eclipse, he told them that his god was angry and would show them that evening. When the moon was eclipsed that night, the islanders promised to continue providing for them, if Columbus' god would restore the moon.

In Chinese mythology, lunar eclipses occur because the Dragon, a masculine solar energy, is attempting to eat the moon. To counteract this effect, it was traditional in ancient China to make loud noises (e.g., bang drums) to frighten the Dragon away. As recently as the nineteenth century, the Chinese navy fired its cannons during a lunar eclipse because of this belief.

SUMMER 2015

THE DARK NIGHT OF THE SOUL

Saint Mary Magdalene, Saint Peter from the Master of Palazzo Venezia Altarpiece Panel, artist unknown. 1350. National Gallery, London. The 'myrrh-bearers' is a group of first century women who assumed various roles in the events surrounding the crucifixion, entombment and resurrection of Christ. However, the most significant role of the myrrh-bearers is as first witnesses to the resurrection. Post-crucifixion narratives detail the discovery of the empty tomb by several women and their vision of an angel who announced the resurrection. Mary Magdalene is pivotal in these accounts as Christian texts identify her as the first witness of the resurrected Christ. During that encounter, he instructs her to notify the disciples of his return. Consequently, the Christian church recognizes her as "equal to the apostles" or "the apostle to the apostles".

Shrouded by the night

And by the secret stair I quickly fled

The veil concealed my eyes

while all within lay quiet as the dead

"The dark night of the soul" by Loreena McKennitt; inspired by the poetry and writing of St. John of the Cross[originally published Summer 2008]

Life evolves in seven year cycles. If you have lived long enough, you can probably identify them. Find a major event from your past -- a marriage or possibly a serious illness. Counting forward or back, see if you experienced another major Life event at the next seven year juncture. If you continue counting, a road map of your life emerges. I am at the end of a seven year cycle. This one was unusual in that the change and disruption, which is usually associated with the first and seventh years, have held steady throughout it.

This cycle probably marks the transition period between the first part of my life where I had all the answers -- to the second part of my life where I have mostly unaswered questions. A little explanation. There was a time when I could describe the paradigm for my life rather simply (to whomever might care to listen). Drawing a triangle on whatever was handy -- a paper napkin, a drugstore receipt, the margins of a takeout menu -- I would explain my life as wife, mother, and artist - with each role occupying a point on the triangle. In the center God resided. That triangle, I insisted, gave my life clarity and meaning, was the model for living which would guide me through the rest of my life. Like I said, I had all the answers. Over the years I explained my paradigm many times to various people. However, during the summer of 2001, the paradigm fell apart.

Which brings me to the Greek myth of Sisyphus and the rock.

Sisyphus was a cunning trickster who loved the pleasures of mortal living. Therefore, when Death came for him, he tricked Him into donning His own shackles. Death remained captive until Ares, the god of war, freed Him. Death then came a second time for Sisyphus. Before leaving the earth, Sisyphus instructed his wife to leave his body unburied. When he arrived in the Underworld, he petitioned Persephone, Queen of the Dead, for permission to return to earth to make arrangements for his burial. She granted his request. Upon his return, however, he neglected his burial and engaged again in the earthly delights. Not long after, Death came a third and final time.

When Sisyphus arrived below, the gods punished him for his willfulness by sentencing him to roll a large boulder to the summit of a high mountain. Since Sisyphus was a powerful mortal, he might have accomplished the task on the first attempt. However, each time he pushed the boulder to the summit, the stone slipped from his grasp and rolled back down to the base. And in this way, the gods exacted their justice from Sisyphus.

The myth of Sisyphus has intrigued philosophers and artists for millennia. According to Albert Camus, Sisyphus is the absurd hero and in the realm of the absurd, there is neither meaning nor eternity. We labor, much like Sisyphus, at futile, repetitive tasks. Therefore, what counts is not the best living but the most living. In this world view, if one wishes to be truly free, one must abandon all hope of meaning or conquest of the summit: the struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man's heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.

Camus holds that this absurdist approach to life elevates an individual. However, I find it limiting. Irritating, actually. In all fairness to Camus, in The Myth of Sisyphus, he does leave room to vary with his conclusion when he states that myths are made for the imagination to breathe life into them. In other words, an individual must discover a personal interpretation for a collective myth in order for that myth to come alive. Therein lies the key.

Looking back, I can identify certain myths or mythic symbols which have marked periods of my life. My childhood fascination with Pegasus began when I read about him in a book on Greek and Roman mythology. While most other little girls gravitated to glass slippers and Prince Charming, I dreamed of adventures on a winged horse. My parents still associate that symbol with me. A small brass Pegasus, a more recent memento from my mother, hangs from the column of a lamp in my New York apartment.

Following the birth of my second child, the butterfly held special meaning. In fact, the resonance of that symbol inspired me to name our family home, a crookedy sharecropper's cottage that we renovated north of Atlanta, "Butterfly Cottage." In the areas immediately adjacent to it, I also designed and planted a series of gardens which featured a wide selection of shrubs and flowers noted for their ability to attract butterflies. Camus would likely hold that the cottage and those gardens were the ways I breathed life into a personal myth.

Which brings me back to seven year cycles.

When my paper napkin paradigm fell apart seven years ago, for all intents and purposes, my myth became the myth of Sisyphus, rolling a boulder toward the summit, in a world where meaning and the eternal did not exist. My belief in God evaporated and not in some transitory way but in a fundamental life-altering kind of way. About eighteen months ago, rather than struggle mightily against the absence of God in my life, I began accepting that God would not return (and quite possibly didn't exist). And a very unexpected thing happened after that: my suffering began to lift. That seems to argue somewhat in favor of Camus' premise that when we let go of our quest for transcendent meaning we will cease to suffer. Speaking for myself, however, it wasn't that simple. Yes, I felt less pain but since there was no divine glue to hold my new paradigm together I felt rather soulless -- or as Jean-Paul Sartre described it, I had a God-shaped hole ... where the divine used to be.

What I have only lately come around to seeing is that the absence of God can, paradoxically, still be a state of grace. Albeit, rough grace.

Is it possible to transform the myth of Sisyphus?

Over the next six months, as I trudged along, that question was foremost in my mind. It seemed there was no getting around it. You might have random moments of joy but if you really accept the myth, it is not possible to transform things -- only to change your attitude toward them. Much to my surprise a quiet and unexpected breakthrough dismantled that notion.

I was spending time studying and writing about Odilon Redon. My love for this painter began about two years ago when I saw his Parsifal (1912), the archetypal Arthurian fool, in the Musée D'Orsay. Since that encounter with Parsifal, I have come back to Redon many times, looking at his artwork, reading about his life. In May I found another Parsifal -- the 1891 lithograph Parsifal I, and there is an interesting story behind that image.

Some art historians believe that the first stone, which Redon used for Parsifal I, was either flawed or broke late in the artistic process. The theory goes that from the broken stone, Redon formed another image: The Druidess (1891). The intimate mythological link between hero and prophetess which Redon created provides a rich context with which to consider these lithographs. It also gives me a framework for my own interior makeup. But more than that, it gives me an extraordinary way of reflecting on the nature of a stone, that it contains many potentialities and when it breaks they emerge.

I think I might be a Christian after all.

I said it aloud last spring while walking across the living room of my apartment. By the time I had crossed from one side of the room to the other, I had also crossed over from an old myth to a new one.

My relationship to my faith has undergone many transformations, as is usually the case by the time you reach adult mid-life. The Christian church has been an important part of my life, not only as a source of community but as a source for the mythology which guides me. When my faith fell away seven years ago, the events of my life were certainly a factor but that is not the complete picture. At that time, I was also feeling increasing alienation toward the patriarchal predilection of the church. My living room revelation did not solve that conundrum. I have not yet figured out how we go about elevating the sacred feminine in this world so that she is face to face with her masculine counterpart. However, I am better able to tolerate the tension of that inequity and do what I can personally to reverence Her. What happened as I crossed into a new myth recently was about something altogether different. It had to do with my Sisyphean rock.

In the flash of those few seconds while crossing my living room, I remembered the story of the resurrection of Christ. After his crucifixion he was buried in a tomb. Possibly because government officials feared that his disciples would steal the body in an attempt to stage a miracle, they ordered a large stone rolled across the tomb's entrance and a small group of guards stationed out front. At dawn on the third day following the crucifixion, Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of Christ, and Salome approached his tomb to redress the corpse. As they neared the entrance, they discovered that the guards were gone, the stone had rolled away, and the tomb was now open. An angel sitting on the discarded entrance stone greeted them and then proclaimed the resurrection. In that remembered story I saw an ancient truth that I could rebuild my life on.

Last summer I was sitting over coffee at a Starbucks on Manhattan's Upper Westside talking with a friend about the paradigm for my life. Using a triangle, I explained that my life can be described as a series of relationships with my self, other people and the planet - with each relationship occupying a point on the triangle. Encircling it all is the transcendent God. And at that time I realized that I finally had a new paradigm that I could rebuild my life on.

It is now almost one year later and I am embarking on a new cycle. And for whatever new questions this next cycle might pose, I believe my life has meaning again and I have found a way to reforge my relationship with the Divine. It would seem that we can transcend the stone of Sisyphus -- after all.